Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS)

Causes / Inheritance

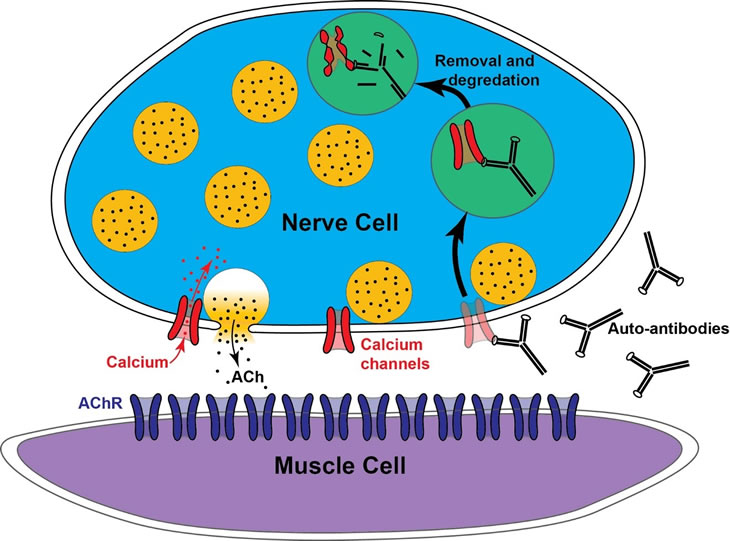

At the normal neuromuscular junction, a nerve cell tells a muscle cell to contract by releasing the chemical acetylcholine (ACh). This release of ACh is triggered when an electrical spike of activity (action potential) reaches the end of the nerve and opens voltage-gated calcium channels that allow calcium ions to enter the nerve terminal. These calcium ions bind to a protein on Ach-containing vesicles, triggering the release of ACh.

After release from the nerve ending, ACh diffuses across to the muscle cell and binds to ACh receptors (AChRs). These receptors are pores that open after binding ACh, allowing an inward flux of electrical current that triggers muscle contraction. These contractions enable someone to move a hand, to dial the telephone, walk through a door or complete any other voluntary movement.

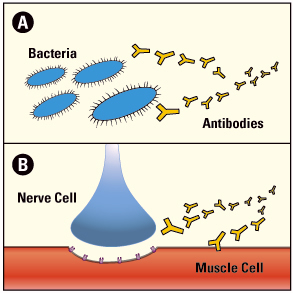

At the ending of the motor nerve, electrical activity normally opens calcium channels (red) that allow calcium ions to enter the nerve ending and trigger the release of acetylcholine (ACh) contained in vesicles (yellow circles). LEMS occurs when the immune system makes antibodies that selectively attack calcium channels. This leads to their internalization and destruction. As a result, in LEMS there are fewer calcium channels at nerve endings, leading to a reduction in ACh release and resulting muscle weakness.

While myasthenia gravis (MG) targets the ACh receptors on muscle cells, LEMS targets voltage-gated calcium channels on the nerve endings to interfere with the trigger for ACh release.

Some 85 to 90 percent of people with LEMS test positive for antibodies against the P/Q subtype of voltage-gated calcium channel, a specific subtype of calcium channel enriched at the nerve endings of motor neurons that control muscle contraction. These autoantibodies made by the person’s own immune system bind to the calcium channels on nerve endings, leading to their internalization and destruction. As a result, people with LEMS have fewer calcium channels on their nerve endings. This results in less calcium entry during nerve activity, and since calcium is the trigger for ACh release, patients have less ACh release. When this ACh release drops to levels low enough that there is not enough to cause a muscle contraction, weakness occurs.

In cases where LEMS is associated with small cell lung cancer, it is thought that these cancer cells make the same types of calcium channels as motor neurons. This is because small cell lung cancer cells are derived from neuroendocrine cells in the lung that also use calcium to trigger the release of chemical messengers. Therefore, when the body’s immune system recognizes these cancer cells as a threat, antibodies are generated against the cancer cell proteins in an attempt to fight the cancer. These antibodies accidentally also recognize the same types of calcium channels on nerve endings, resulting in an attack on the motor nerve terminal.

The trigger for LEMS without cancer is unknown, but may have a genetic component linked to autoimmunity. In any case, these patients also make antibodies that target calcium channels, and the neuromuscular disease is the same as in those with cancer.

All people with LEMS are tested for the presence of antibodies in their blood directed against calcium channels, and 85 to 90 percent of those diagnosed with LEMS do have measurable antibodies to calcium channels present. A small percentage of people who are diagnosed with LEMS do not have measurable antibodies to calcium channels. These individuals are referred to as “sero-negative” LEMS patients, and they have antibodies to other proteins that are important for ACh release from nerve endings. Along these lines, all people with LEMS likely have antibodies to other nerve ending proteins in addition to antibodies to calcium channels. Lastly, some people who test positive for calcium channel antibodies do not have clinical signs of LEMS (see LEMS Diagnosis). This may be because the levels of those antibodies are very low.