Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

Signs and Symptoms

Learn about MDA’s COVID-19 response

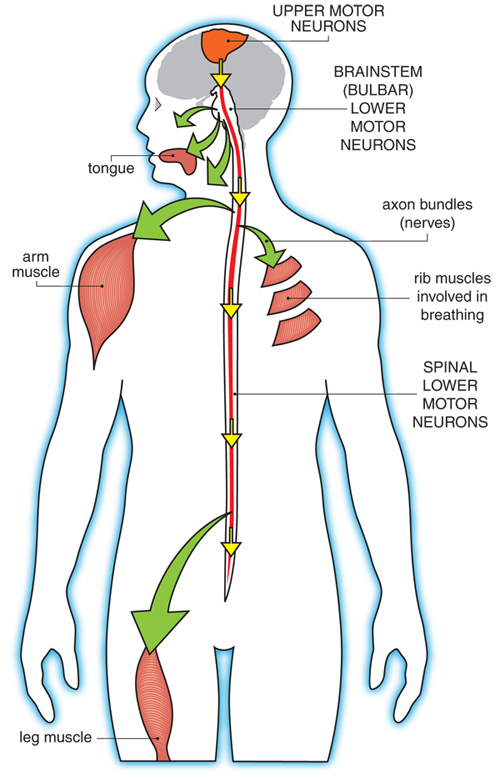

ALS affects the upper motor neurons, which are in the brain, and the lower motor neurons, which are in the spinal cord and brainstem. Upper motor neuron degeneration generally causes spasticity (tightness in a muscle), slowness of movement, poor balance and incoordination, while lower motor neuron degeneration causes muscle weakness, muscle atrophy (shrinkage of muscles) and twitching (fasciculations). These can occur in combination in ALS, as upper and lower motor neurons are affected at the same time.

ALS can affect people of any age, though it usually strikes in late middle age. ALS typically announces itself with persistent weakness or spasticity in an arm or leg (80% of all cases), causing difficulty using the affected limb. Sometimes (in about 20% of all cases) the problem presents first in the muscles controlling speech, producing alterations in the vocal quality, or swallowing, which may lead to coughing and choking. The disease can also affect the muscles of the face, leading to problems such as incomplete eye closure and drooling. ALS can even manifest as inappropriate laughing, crying, or yawning (pseudobulbar affect). 1,2

It is not unusual for people to ignore such problems for some time at this stage, or to consult a physician who may be relatively unconcerned. However, the disease, if it is truly ALS, generally spreads from one part of the body to another so that eventually the problem can no longer be ignored. It is at this point that people usually are referred to a neurologist, who will consider ALS among many other possible diagnoses.

The involuntary muscles involved in the heartbeat and sexual functions are not directly affected in ALS. Constipation, impairment of the stomach, bloating, and urinary urgency can occur in patients with ALS. Prolonged inability to move and other effects of ALS can have also an indirect impact on these organs. Hearing, vision, and touch generally remain normal. Some patients complain about excessive sweating, but the association between sweating and ALS remains controversial.3

Pain can occur as a result of immobility and its various complications, especially if precautions such as daily range-of-motion exercises are not undertaken. Also pain due to nerve affection may occur in some patients with ALS.4,5,6,7

Fasciculations are a common symptom of ALS. These persistent muscle twitches are generally not painful but can interfere with sleep. They are the result of the ongoing disruption of signals from the nerves to the muscles that occurs in ALS.

Some with ALS experience painful muscle cramps, which can sometimes be alleviated with medication.

Some people with ALS undergo alterations in their thinking or may exhibit uncharacteristic behavior changes, often referred to as frontotemporal dementia, or FTD. However, memory loss, a hallmark of Alzheimer's-type dementia, is generally not a feature of ALS. Instead, the person with ALS might be irritable, inconsiderate, apathetic, or impulsive or might otherwise act in uncharacteristic ways.

Another potential ALS symptom — not experienced by all — is a temporary lapse of control over emotional expressions such as laughing or crying, a phenomenon called pseudobulbar affect. Laughing or crying bouts, often triggered by the smallest of things, are more related to the disease process rather than to actual feelings of happiness or sadness. Medications such as Nuedexta and various other strategies can help manage this symptom.

For more about the progression of ALS symptoms over the full course of the disease, see Stages of ALS.

References

- Thakore, N. J. & Pioro, E. P. Laughter, crying and sadness in ALS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry (2017). doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-315622

- R., T. et al. Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) in an incident ALS cohort: results from the Apulia registry (SLAP). J. Neurol. (2016). doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7981-3 LK - http://sfx.library.uu.nl/utrecht?sid=EMBASE&issn=14321459&id=doi:10.1007%2Fs00415-015-7981-3&atitle=Pseudobulbar+affect+%28PBA%29+in+an+incident+ALS+cohort%3A+results+from+the+Apulia+registry+%28SLAP%29&stitle=J.+Neurol.&title=Journal+of+Neurology&volume=263&issue=2&spage=316&epage=321&aulast=Tortelli&aufirst=Rosanna&auinit=R.&aufull=Tortelli+R.&coden=JNRYA&isbn=&pages=316-321&date=2016&auinit1=R&auinitm=

- Kihara, M., Takahashi, A., Sugenoya, J., Kihara, Y. & Watanabe, H. Sudomotor dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Funct. Neurol. (1994).

- Chiò, A., Mora, G. & Lauria, G. Pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The Lancet Neurology (2017). doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30358-1

- Handy, C. R., Krudy, C., Boulis, N. & Federici, T. Pain in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Neglected Aspect of Disease. Neurol. Res. Int. (2011). doi:10.1155/2011/403808

- Goy, E. R., Carter, J. & Ganzini, L. Neurologic Disease at the End of Life: Caregiver Descriptions of Parkinson Disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Palliat. Med. (2008). doi:10.1089/jpm.2007.0258

- Veronese, S., Valle, A., Chiò, A., Calvo, A. & Oliver, D. The last months of life of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mechanical invasive ventilation: A qualitative study. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. (2014). doi:10.3109/21678421.2014.913637