The FDA Approval Process: Can We Have This Drug Now?

Questions and answers about the FDA and its process for approving drugs

To people faced with life-threatening diseases, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can seem like an indifferent obstacle, keeping them from treatments that would otherwise be available. But the reality is much more layered and complex.

Here, MDA answers some frequently asked questions about how the FDA works to shed light on this topic.

Q: Why does the FDA have stringent regulations regarding the safety and efficacy (effectiveness) of drugs?

Q: Why does the FDA have stringent regulations regarding the safety and efficacy (effectiveness) of drugs?

A: The FDA’s goal is to protect people from unsafe or ineffective drugs. A short glance at history reveals a lot about why the FDA came into being in 1930 and has survived into the 21st century. Two examples stand out — the deaths in the late 1930s of more than 100 people who took an infection-fighting drug that was unfortunately dissolved in a deadly poison, and the birth in the 1960s of babies with limb deformities after their mothers took what seemed to be a harmless pill (thalidomide) to treat their pregnancy-associated nausea.

And throughout history, vulnerable patients have been lured by expensive treatments that may or may not have harmed them but resulted in serious financial setbacks or kept them from seeking other, possibly helpful, remedies.

It is from this history that the FDA has developed its current standards of safety and efficacy for medicines and medical devices.

Q: Does the FDA realize there are individuals and families who are counting on new drugs to save their lives? Can the review and approval process be made faster when lives are at stake?

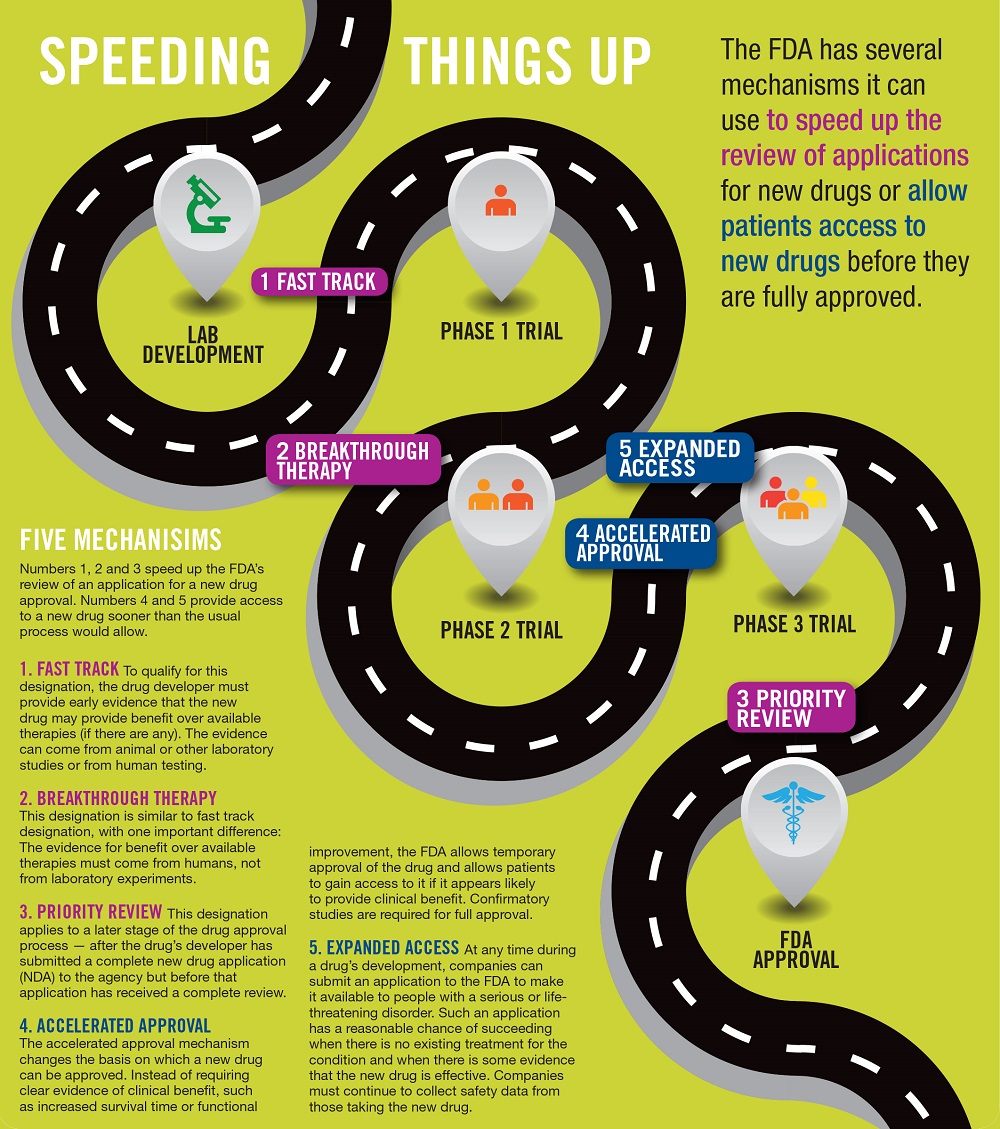

A: Yes. The FDA has mechanisms for speeding up the process it uses to review developers’ applications for new drugs. These include “fast track,” “breakthrough therapy” and “priority review.” In addition, the FDA can supply an investigational drug to patients through its “expanded access” mechanism and can allow access to a drug that is not fully approved through its “accelerated approval” pathway. (For more, see Speeding Things Up on this page.)

Q: Can the FDA alone provide access to an unapproved drug?

A: No. The FDA can provide a legal pathway for access to a drug that is not fully approved, but it cannot make the company behind that drug supply it.

Q: What are the risks to a company of supplying a drug that has not gone through the full approval process?

A: According to drug companies, supplying a drug to patients before it is fully approved can be very risky, especially for a small firm with limited resources. Companies depend on having a fully approved product on the market or at least a clear path laid out for that goal. That’s how they attract investors, and that’s how they stay in business.

When supplying a medication that the FDA has not fully approved, the developer of the medication runs several risks, including:

- not being able to successfully conduct clinical trials required for approval, since patients have the opportunity to obtain the drug without participating in a trial;

- difficulty meeting high demand for a limited supply of the drug;

- not having the necessary funds to take the drug through the approval process because so much money had to be spent on manufacturing and distribution for an expanded access program; and

- not being able to carry out the necessary trials needed for full approval because of adverse events that may have occurred in patients taking the unapproved drug (although the FDA says it knows of no such examples).

Q: What are the risks to patients taking a drug that has not been approved or has been approved through an accelerated approval pending confirmatory studies?

A: To the family of a loved one facing a fatal disease, all risks associated with unproven treatments may seem worth taking. Unfortunately, many people who try unproven drugs actually get worse.

Q: Are there ways that this process could be improved?

A: Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist based at New York University, believes the process could be improved by developing a standard template that patients and families could use to apply for access to unapproved drugs and establishing an independent advisory board consisting of patient advocates, scientists and ethicists to review such requests. The board, Caplan proposes, might help small companies get over the financial hurdles associated with providing an experimental drug to patients by supplying funding derived from taxes on the industry or from government funding.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information