Despite Muscle Disease, 'Toy Tiger' Was an Awesome Fighting Machine

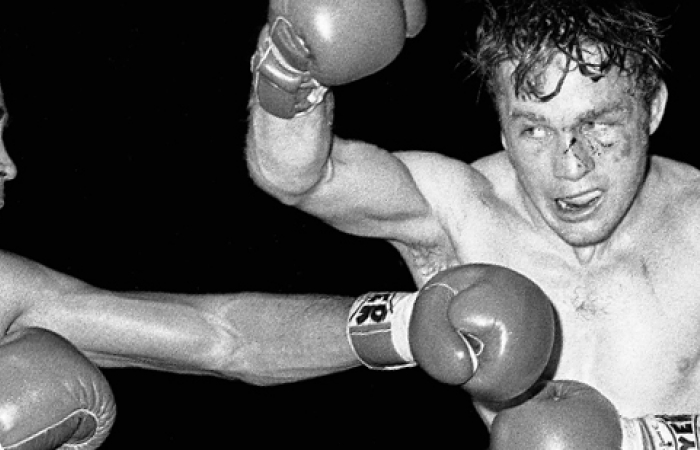

In a bloody 1975 bout Hafey (right) successfully hammered Salvador Torres to a win in 10 rounds. Photos courtesy of Brad Little.

Art Hafey knew, from the way his arm and leg muscles were knotting up uncontrollably, that he’d never be able to go the full 10 rounds with hard-punching Vicente “Yambito” Blanco.

So Hafey did what he had to, in the characteristic bone-crushing fashion that had driven him to the top of professional boxing’s Featherweight Division: He knocked out his opponent in the fifth.

That was 1975 in California, at the height of what boxing fans came to know as the West Coast Featherweight Wars.

Disease? What disease?

Incredibly, especially considering his ranking in the sport, Hafey had the neuromuscular disease myotonia congenita (MC), although he didn’t know it then.

Caused by mutations in a gene that carries instructions for a chloride channel, MC leads to delayed muscle relaxation, muscle stiffness and involuntary contraction of muscle, typically provoked by sudden movements after rest.

The classic example of the disease’s effect is the case of a person who shakes hands with another person, but then is unable to let go.

Hafey battled on to greatness despite his disease; his full story was captured in a 2009 documentary titled "Toy Tiger."

“Toy Tiger” is both inspirational and disheartening. It’s the story of a diminutive brawler (Hafey stands 5’2”) from Nova Scotia who out-punched men much bigger than he, gradually learned fighting finesse, took down the best featherweight fighters in the world — and then was denied a shot at the championship title.

Hafey’s story is richer than fiction. The 98-minute documentary touches on the highlights of Hafey’s career and is accompanied by a second DVD with hours of footage from other early classic fights.

Boxing vs. baseball

Hafey and his older brother Lawrence both got into boxing when Art was 12 because they’d tried playing baseball and couldn’t handle it. “As soon as I hit the ball and tried to run to first base, I’d fall flat on my face,” Hafey recalled. His disease (the rarer form of MC, known as Thomsens disease), was playing havoc with his muscles.

The boys’ father was a boxing fan, and he had to have been proud when, at age 14 and all of 75 pounds, Art was named Paperweight Champion of Nova Scotia.

Hafey went on to clear out all of the competition in his amateur weight class in Canada’s Maritime Provinces. “I knew absolutely nothing about technique or delivery,” he said during a recent phone interview. “Just wild haymaker punches.”

Seeking new opponents

Hafey’s manager sought new opponents for his young slugger in Quebec City, and boxing promoters there soon regretted their initial willingness to accommodate him. By 1968, 17 years old when he turned pro, Hafey was 116 pounds of deadly force.

In his first notable fight in Quebec, against Paul Tope, who later became Canada’s No. 1 lightweight contender, Hafey was the underdog. “They had scheduled it for six rounds, thinking I’d be history by that time. Then suddenly, when I was still going strong in the sixth, they announced it would be a seven-round fight, instead,” he recalled. “I guess they figured Tope would take me out for sure in the seventh. That’s when I knocked him out.”

Hafey had gotten a taste of the shady dealings and shenanigans that have pervaded professional boxing since its beginnings. It wouldn’t be his last.

The move to California

In Canada, Hafey was paired up with opponents who were 10 to 15 pounds heavier than he, because others of his weight didn’t want to tangle with him. He was cleaning their clocks, but his manager knew it was only a matter of time before he got hurt by a heavier fighter.

Quebec City promoters deliberately tried to get Hafey into the ring with far heavier opponents because they wanted to literally knock him out of competition, said Brad Little, the producer/director of “Toy Tiger.” Little spent five years combing through hundreds of hours of old films and still photos to create the documentary, which includes present-day interviews with Hafey, other fighters, trainers, managers and promoters from the 1970s.

The Hafey team shifted its action to California in 1972 (“the best move of my career,” Hafey said) where a dynamic cadre of featherweight fighters, many of them born in Mexico, was delighting the boxing world with furious fighting energies and flamboyant social lives.

Into that maelstrom of talented pugilists and party animals stepped the Canadian guy who didn’t smoke, drink, cuss or chase women. He just had a powerful desire to succeed in the ring.

’The Executioner’

In his first major California fight, in 1973, Hafey’s opponent was highly regarded Octavio “Famoso” Gomez. Hafey got knocked to the canvas twice in early rounds, then unleashed a barrage of punches that opened up a serious cut above Gomez’ eye and stopped the fight. The Gomez fans were furious, screamed obscenities and threw bottles into the ring. They didn’t like this spoilsport of a newcomer.

In coming fights, Hafey acquired the nickname of The Mexican Assassin or The Executioner, for the number of Mexican fighters he vanquished. He also was known in Canada as the Toy Bulldog, and in the United States as the Toy Tiger. Because of his ancestry, some called him Irish Art. His boxing trunks were adorned with shamrocks.

Muscle with no effort

Hafey was never a weight lifter, but nonetheless had the physique of one (including a 17-½-inch neck) due to the effects of his involuntary muscle contractions.

Myotonia congenita often affects people shortly after periods of rest. Because that frequently happened to Hafey at the end of a round after he’d gone to his corner for a break, he often didn’t sit on the stool in his corner. Instead, he’d remain standing, unrelaxed, hoping to avoid further contractions.

The disease also, ironically, often strikes when a person’s adrenalin is flowing, as it had to be much of the time Hafey was in the ring. “There were two times I noticed it the most,” he said. “If I had to chase my opponent [rather than standing toe to toe trading punches], I’d start to tighten up. Same thing if I trained too hard.”

Training too hard, according to Little, often occurred when Hafey was trying to “make weight.” If he was a few pounds over the featherweight limit (then 126 pounds), he might have to exercise hard for hours to drop weight. In those cases he could be fatigued, muscles clenched up, at fight time. Back then, fighters were officially weighed on the day of the fight, unlike today, where they’re put on the scales the day before.

Below the belt

In 1974, promoters set up Hafey for a fight in Nicaragua that he said never should have been allowed. His opponent, ostensibly a featherweight, was Alexis Arguello. “He stood 5-feet-10, and I can tell you he was heavier than any featherweight,” Hafey vividly recalled. “I took a beating, and they stopped the fight in the fifth, but it was a sham. Every time I went to the inside, under his punches, where I could work on his body, the ref pulled us apart and told me to keep my head up. He knew where my power was, and he wouldn’t let me use it.”

Because of his height, and arms that seldom were as long as those of his opponents, Hafey couldn’t rely on the jab to land his punches. He had to get inside the longer reach of his adversaries where, ideally, he could throw sequences of hooks to the body, followed by uppercuts.

Hafey was able to elicit one rueful aspect of humor from his experience in Nicaragua: “In one respect I’m glad I didn’t win. They had guys with submachine guns at ringside. If I had taken out their boy, they might have shot me.”

Based on that dubious win, Arguello was given a crack at fighting the reigning featherweight champ for the title.

The best year

Hafey was a shining star in 1975. “Art went 11-0 during 1975, retired the former junior lightweight champion of the world with a fourth-round KO in Caracas, destroyed a top contender in front of a record 18,000-plus people and ended the year as Ring magazine’s No. 1 contender for the featherweight title,” Little said in an e-mail.

But even though Hafey was at his best, other less-talented featherweights were getting a crack at the title.

Never a title shot

There is plenty of speculation as to why Hafey didn’t get his chance, but the majority of opinions revolve around the fact that he was just a little too “clean” for the organizations and people who ran professional boxing.

Hafey said, “Somehow I alienated some very influential people. They eventually refused to acknowledge me, even though they knew I was the top contender. If you’re not connected with the right people, it’s almost impossible to make it, whatever business you’re in.”

The dream bubble bursts

In December 1975, Hafey went home to visit family in Nova Scotia, and while there had an operation to repair a double hernia. About two months later, before he felt fully ready for it, he fought Rodolfo Moreno. Hafey won the fight, but it was brutally damaging to both boxers.

Hafey’s face was badly swollen, and he knew he should have seen a doctor immediately, but his team wanted to go out and celebrate instead.

Whether it was from that fight, or one in that general time frame, Hafey had suffered a brain hemorrhage and lost part of his vision in both eyes.

He fought only three more times, then called it quits at 26 years old.

He had fought 409 rounds in 65 fights, of which he won 53 (36 by knock out), lost eight and had four draws. He had never suffered a cut that required a stitch.

“Art had a great career, just by the numbers,” Little said. “If he had known then what he does now, he might have been able to structure his diet, plan his exercise schedule — he could have been the greatest.”

Hafey and Muhammad Ali have the same birthday.

Into 33 years of quiet

With money he’d saved, Hafey bought some apartments in Nova Scotia, married one of his tenants and has lived a simple and frugal existence for more than three decades, never asking for more fame than he’d been allotted, never protesting that he’d been robbed of greatness.

Myotonia congenita is not a progressive disease; its symptoms don’t get worse over time. Hafey has learned how to live with it even though it still is debilitating. When speaking he sometimes has to halt for a few moments because his throat muscles tighten up. His vision loss from the Moreno fight was permanent, but he can drive if he concentrates.

Return to the limelight

“Toy Tiger” may mitigate some of the injustice Hafey suffered.

When the documentary debuted in Hollywood on Oct. 9, 2009, and then premiered in Nova Scotia on Nov. 23 to an overflow crowd of more than 700, many of Hafey’s old boxing buddies were on hand to congratulate him on finally having his story fully told. Some of his former opponents have died. Some of those still living are showing the signs of “fighter’s dementia” that results from having your head hit hard too often.

Former boxer Randy De La O summed up the sentiment on the Oct. 9 occasion in his blog (http://boxing-ring.blogspot.com/2009/10/toy-tiger-premier-el-portal-thea...), when he wrote, “I remember Art Hafey as a humble, quiet, polite, reserved and respectful person. Thirty-three years later, that is still my impression.”

Art Hafey was inducted into the Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame in 1980, and into the California Boxing Hall of Fame on June 26, 2010.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information