Simple and Safe

Noninvasive volume ventilation systems go beyond 'BiPAP'

Editor’s note: In the last issue of Quest, Diane Huberty told readers why she was happy with getting her breathing assistance (ventilation) through a tracheostomy tube with a volume ventilator (see “Truth, Lies and Tracheostomies,” July-August 2007). In the following article, Michael Munn tells readers why he prefers having a mask or mouthpiece with the same type of ventilator.

The February morning began pretty much like any other — shower, dressing, breakfast, and then to my desk at home. But what happened around 10 a.m. was not like any other morning. I felt shorter and shorter of breath. I was moments away from calling 911 when I relaxed and began to breathe more easily.

Over the next few months, though, things got worse. At one point, while we were shopping in a mall, my wife left me momentarily. She returned to find me slumped over in my wheelchair, barely conscious and incoherent. I never would have guessed a breathing problem could cause this. But it can and does.

Having experienced weakness from limb-girdle muscular dystrophy since my teen years, I'd expected to lose the ability to climb stairs, stand up from chairs, stand up from the floor, and even to walk. I fell countless times during all those years. In more than 50 years I've had hundreds of falls. But breathing was never a problem.

By the time the summer of 2001 rolled around, it was really serious. Lung tests and overnight sleep tests turned up two problems. The first was that my diaphragm muscles were weakening and easily tired. The second was the discovery that I have central sleep apnea (CSA), a condition in which the brain doesn’t tell the muscles to breathe during sleep. It leaves the body gasping for air, but I didn’t know this was happening.

Starting out: Noninvasive pressure ventilation

There are basically three options for breathing support — noninvasive pressure ventilation, noninvasive volume ventilation, and invasive (tracheostomy) volume ventilation.

The near-term solution offered to me was nighttime noninvasive pressure ventilation with a mask. You’ll hear these systems referred to as “BiPAP” devices, which stands for “bilevel positive airway pressure,” even though that’s actually just the name of the Respironics brand.

Many patients start with this type of breathing assistance. It may work for moderate respiratory muscle weakness, but it can’t deliver very much air.

With bilevel pressure ventilation, the machine pushes air into the lungs at a constant pressure. It then drops down to a lower pressure to allow breathing out. The pressure pulse always strained my throat and lungs, sometimes painfully. It worked well for my condition because the machine forced me to breathe during times when my brain didn’t tell me to breathe.

My diaphragm muscles also got a good rest during the night. For about a year this all worked. I felt much better during the day — no tiredness, no falling into a semiconscious state, no more slumping over.

Then, I began having more and more difficulty breathing during the day. I wheeled into the bedroom to use the machine every hour or so. It was clear another threshold had been crossed. It was time for something else.

Moving on: Noninvasive volume ventilation

The next step could have been invasive volume ventilation - i.e., ventilation delivered through a tracheostomy (trach) tube, which is surgically inserted through a hole in the trachea (windpipe).

But for me it was noninvasive volume ventilation, delivered through a mouthpiece or mask. My main concerns about tracheostomy systems were the possibility of infections and hospitalization, and the extra burden my trach care would place on my wife.

Volume ventilation delivers a set volume, rather than a set pressure, of air to the lungs, with each “breath.” Volume-cycled ventilators can deliver higher volumes and higher pressures of air than the maximum possible with BiPAP-type pressure-cycled devices. (Editor’s note: Some modern ventilators, such as the Pulmonetics LTV 950 and 1000, can be set to limit either pressure or volume and are more powerful than a BiPAP-type device.)

The only difference between noninvasive and invasive volume ventilation is how the air is delivered. The ventilator is the same.

The first thing I noticed was how much better volume ventilation felt than pressure ventilation. I thought the painful breathing with pressure ventilation was normal for machine-supported breathing. It is definitely not normal. Volume ventilation passes a set volume of air into the lungs with a gentle rise in pressure, just like natural breathing.

Finding the right mask

The key to finding a mask that works well is a patient and helpful respiratory therapist. Because of the large market for people with breathing problems like sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, manufacturers make a staggering variety of masks to use with BiPAP. These can be used with volume ventilators with a simple modification.

BiPAP masks have exhaust ports (tiny holes in the mask or tubing) to prevent rebreathing of exhaled air. With volume vents, the breathing circuit removes this air. To avoid leaks, you have to cover the exhaust holes with medical tape.

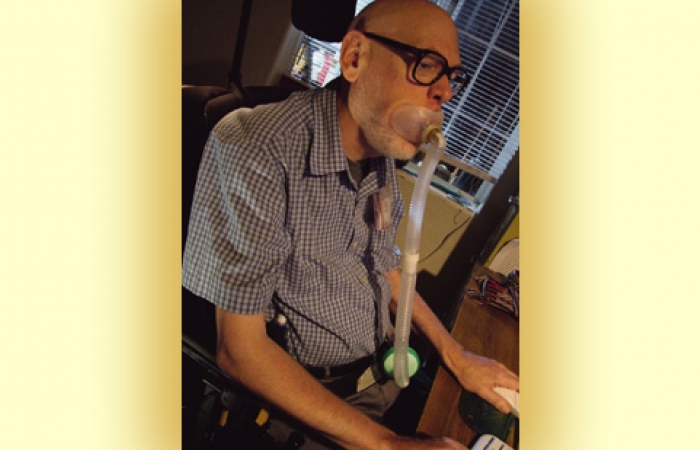

We went through quite a few masks and mouthpieces until I settled on an oral interface (mouthpiece) for daytime use and a mask with a gentle, air-supported seal to minimize leaks for night.

The zero-leak oral mask is so easy to use and comfortable that I now often use it both day and night. It has an inner flap that goes inside the mouth. I don’t need any effort to keep it in place while I’m awake. A strap is available to keep it in place during sleep in case I push it out with my tongue.

I can easily remove it to talk, eat, drink or just to relax without it for a time. (The vent keeps running on standby.) The time I can stay off-vent varies. Sometimes I can go two or three hours. At other times I start turning blue in 15 minutes. If I’m tired or ill, I know I need to stay on as much as I can. Half an hour or an hour for daily activities is usually no problem. I can be off-vent to use a computer speech recognition program or my computer phone.

Whether or not a mask is ugly is in the eye of the beholder. The real question is: Do you care what other people think? With the variety of masks available, it’s possible to find one that’s comfortable and not unsightly. (Some masks are very uncomfortable and can even cause pressure sores and skin breakdown. Don’t settle for one of those.)

Early on, there may be a feeling of suffocation or feeling “closed in.” This passes with time. Persistence pays off.

Ordinarily, the cost of masks, which need to be replaced every few months, is covered by insurance. Some people use custom-designed masks that are created from molds of their face. These masks can accommodate unusual facial shapes, but it may be difficult to get insurance to cover them.

Almost no care required

Care of noninvasive ventilation equipment is easier than for invasive equipment. There is no trach or cannula cleaning; nor is suctioning needed. Masks are rinsed daily and then sanitized once a week.

Vent-related personal care is nonexistent, because there's no "wound" to keep clean. It's much simpler for the caregiver, and anything that eases that burden is worthwhile. Also, I've found that some home-care companies will not provide service if the patient has a trach.

Breathing circuits — tubing and couplers — are changed every two weeks. A small filter and humidifier (which simply plugs into the tubing) is replaced as needed, usually every three or four days.

For night use, most people need a heated humidifier chamber (usually provided with the ventilator), which must be filled with sterile water every night.

If secretions become a problem and natural coughing is ineffective, a noninvasive device called a CoughAssist can be used. A CoughAssist delivers a powerful breath of air to the lungs and then reverses the pressure, pulling secretions with it.

I’ve read in the medical journal Chest and been told by my doctor and respiratory therapists that the typical tracheostomy patient develops an infection requiring a hospital stay two or three times a year, while the typical noninvasive volume vent user needs infection-related hospitalization on average once every two years.

I've never had an infection requiring hospitalization in my five years of using noninvasive ventilation.

Does NIVV do the job?

Noninvasive volume ventilation and invasive (tracheostomy) volume ventilation work equally well for most people, judging by achievement of correct oxygen and carbon dioxide blood levels. But noninvasive ventilation is far more comfortable, in my opinion. (I’ve seen people being suctioned, and I’ve seen infections, and neither looks comfortable to me.)

Oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the blood tell how well a vent system is working. It’s easy and painless to monitor blood oxygen levels with a tiny device called an oximeter. A level of at least 95 percent is normal. (Many insurers, but not Medicare, will pay for an oximeter.) Some models will record levels throughout the day or night.

Getting what you want

The largest barrier to obtaining noninvasive volume ventilation is that many doctors feel the choice is only between a BiPAP and tracheostomy-delivered volume ventilation. They don’t seem to be aware of noninvasive volume ventilation.

I discovered that, once your doctor is aware of the option, it’s really not too hard to obtain and use this type of equipment. In fact, BiPAP requirements are much harder to meet than those for volume ventilators.

Under Medicare:

- Your regular doctor or primary care provider can write the letter of medical necessity (samples are readily available online);

- insurance covers two ventilators (one at bedside and one on the wheelchair); and

- all accessories, such as batteries, breathing circuits, filters and masks, are covered.

In my case, with Medicare and secondary insurance, my out-of-pocket expense is zero. Others may need to add a co-pay.

You can always switch to a trach

Noninvasive volume ventilation is the answer for many people with neuromuscular disease who need something more than BiPAP.(Editor’s note: Trachs are often needed in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other conditions in which the muscles of the mouth and throat are severely affected. In these disorders, it may not be possible to deliver air reliably from the nose or mouth to the lungs.)

Should conditions or preferences change, a decision to proceed to tracheostomy-supported breathing is always possible.

Should conditions or preferences change, a decision to proceed to tracheostomy-supported breathing is always possible.

In the intervening time, daily life with noninvasive ventilation is as close to normal as one can get while relying on machine aids for breathing. So, if breathing becomes a problem, be persistent, ask questions, and know there is an answer that will work just right for you.

Michael Munn, 62, holds a doctoral degree in astrophysics and is a retired chief missile defense scientist who lives in Benson, Ariz., with his wife, Kay. He has published articles in professional journals on energy expenditure and caloric needs of people with neuromuscular disease who are using ventilators. Munn was the MDA Personal Achievement Award recipient for Arizona in 2005.

For more information, see "Truth, Lies and Tracheostomies," July-August 2007; "The Great Trach Escape," September-October 2003. Always check with your doctor about assisted ventilation options for your condition.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information