Truth, Lies and Tracheostomies

When neuromuscular disease weakens the muscles used for breathing, many people benefit greatly from noninvasive ventilation (NIV), which can add years of breathing support.

But when a tracheostomy and ventilator are suggested for better breathing, some people see NIV as “enough” and a trach and vent as somehow “too much.”

When a person’s overall quality of life is no longer acceptable, that’s certainly a valid choice. But a trach and vent shouldn’t be ruled out if quality of life problems are due in large part to respiratory problems.

A vent is simply a different, more powerful breathing machine. And a trach (a surgical incision through the neck into the trachea, into which a breathing tube is inserted) shouldn’t be rejected simply based on rumors that it’s complicated, time-consuming,problem-prone, ugly, uncomfortable, expensive, prevents talking or eating by mouth, and is a permanent change.

Why switch from NIV?

NIV assists breathing through face masks, nasal plugs or tubes to “sip” air, without the need for surgery. So why would anyone even consider going to a trach tube?

I successfully used NIV for six years, until a simple cold caused respiratory failure, which led to a trach and vent. NIV can prove inadequate for a variety of other reasons:

- Facial features such as a crooked nose or a deviated septum can make finding a mask that doesn't leak or breathing entirely through the nose difficult.

- NIV may aggravate sinus problems or cause severe abdominal distension.

- Some find anything on the face claustrophobic.

- Facial weakness reduces necessary jaw closure and ability to use a mouthpiece.

- It can take months to find the right mask or device and get used to NIV, so if knowledgeable support or strong motivation is lacking, NIV probably won't work out.

The more common reason for switching, however, is that after successfully using NIV for some time, a person’s breathing muscles weaken further with progression of a severe neuromuscular disease (particularly in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Several symptoms show that this is occurring, such as:

- Frightening spells of suffocating or choking congestion caused by thick mucus and a poor cough. Breath stacking, manual cough assistance or a CoughAssist device work very well for some, but others find these methods minimally effective.

- The hours the person needs to use NIV increase from overnight to most of the day. Going out becomes more difficult because of equipment needs and because wearing the mask in public is unacceptable to some.

- Because pressure-based NIV can only assist breathing, as a person’s breathing capacity deteriorates, he or she slides back into the fatigue, poor appetite and anxiety of pre-NIV days.

- Pneumonia or a simple chest cold result in a respiratory crisis, because NIV is insufficient. NIV delivers air based on pressure sensing, so as the lungs become more congested, the pressure limit is reached more quickly and less air is delivered. A volume-based vent (such as is used with a trach) delivers a full breath regardless of congestion. Volume-based vents can be used with NIV, but this is rarely done, although the practice is growing.

The truth about trachs

First, is a trach really more complicated and time-consuming?

Let’s go through the daily routines of life with a trach:

-

Cleaning around the trach — 30 seconds

This part of trach care is done as part of bathing or washing up. Once-a-day cleaning is enough, unless there’s a lot of mucus drainage around the tube or recurring infections.Gloves are optional, and finding a safe, easy-to-use and inexpensive cleaner for long-term use is easy: Buy soap. An antibiotic soap isn’t necessary.

The 2-by-2-inch gauze pads and cotton swabs used in the hospital can be replaced with clean washcloths. Ointment isn’t needed unless there’s redness or obvious infection.

-

Cleaning the inner cannula — 5 minutes

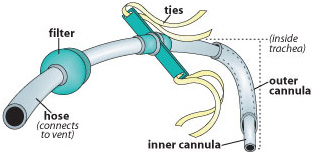

A standard trach tube is actually a tube within a tube. The smaller one (inner cannula) is removed for cleaning daily.Most people can follow a “clean” rather than “sterile” routine: disposable exam gloves, dish soap and tap water. Hydrogen peroxide helps with stubbornly thick mucus. The whole process isn’t necessary at all if you switch to a trach without an inner cannula!

-

Trach ties — occasional

Daily changing isn’t needed. Just change when damp or dirty. -

Suctioning — about 3 minutes

Some patients need suctioning only two or three times a day, others a dozen or more. Everyone has good and bad days. Generally suctioning can be done (by a caregiver) with just one nonsterile disposable glove (not reused) and catheter (changed daily).Suctioning isn’t at all difficult to do. The hard part is getting the suction catheter out of the package, connected to the tubing, the machine turned on, and the vent hose taken off the trach without touching anything but the catheter with the gloved hand!

-

Equipment care — variable

- The suction canister and its tubing are washed with soapy water every other day — 5 minutes

- The vent hoses are chang-ed weekly or every other week and are disposable — 10 minutes.

- The filter and small hu-midifier that fit inline on the vent tubing are changed twice a week — 3 minutes.

- Vent check, once a week — 10 minutes.

- Reordering supplies — 15 minutes once a month.

-

Trach changes — 10 minutes

Frequency of changes varies from weekly, to monthly, to every other month, to “whenever it seems to need it.” It takes about 10 minutes.People prone to granulation tissue (overgrowth of healing tissue) will have easier changes if they’re done frequently. Frequent changes also may reduce respiratory infections. Changing the tube is a very simple procedure that caregivers can do, unless there are problems with an abnormally shaped trachea or excessive granulation tissue.

Are trachs more problem-prone?

It’s misleading to compare problems with trachs to problems with NIV, because people with trachs are nearly always further along in their disease progression. Often, the switch from NIV to trach and vent isn’t a choice, but necessary to go on living.

That said, trachs carry a slight risk of incision infection, and increased respiratory infections are reported. However, in my experience these infections can be more effectively managed than those acquired on NIV, because suctioning is easier and better control of respiratory status is possible.

Coughing caused by congestion is easily relieved with suctioning. In spite of the vigorous cough it causes, suctioning doesn’t hurt — and is a huge improvement over long, exhausting and frightening episodes of trying to cough out a plug of mucus.

Some people are prone to granulation tissue, an excessive growth of new tissue stimulated by the trach incision and presence of the trach tube. This tissue is delicate and bleeds easily and may make trach changes difficult. Granulation tissue can be handled with cortisone, silver nitrate and, in some cases, laser removal. Seek your doctor’s advice.

Ugly and uncomfortable?

Although a sip tube isn’t bad, nasal pillows aren’t exactly nice to look at and NIV headgear looks more “Star Wars” bizarre than “Top Gun” cool.

A trach can be covered with a turtleneck or dickie with a small hole cut for the hose. Both kinds of ventilation have big hoses draped around, but a trach leaves your face free, which for most people is a big social improvement.

After the initial healing period, a trach isn’t even felt unless the vent hoses are pulling on it. That causes a sore throat-type ache that’s immediately relieved by repositioning the hoses. Whenever the trach or vent tubing is moved, it sets off an aggravating but not painful coughing spell.

Discomfort of the skin around the trach indicates irritation or infection and usually is easily treated with ointment.

Most people find trachs comfortable and convenient. The most annoying discomfort is the same as with an NIV mask — air leaks. As with a mask, adjusting the hose position may help, but persistent problems require increasing the size of the trach.

More expensive?

Yes. But it’s very difficult to discuss costs, because cost is dependent on whether the person is covered by Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance or a combination.

Most people find they’re very well, or even completely, covered for ventilator rental, replacement trachs, suction catheters, gloves and other supplies. Others may have a co-pay of 20 percent, or have to buy some supplies, or have any imaginable combination of coverage.

One expense often said to be required is around-the-clock nursing care. Untrue!

It’s true that a person on a vent must have someone available at all times to respond within minutes, but nurses are not required. Anyone, such as a family member, can be taught how to suction and handle vent alarms. (However, for those hiring outside help, many home health care agencies only will provide registered nurses for people with trachs.)

No more talking and eating?

If people were able to talk before being trached, there are options for resuming speech. The simplest way is to deflate the trach cuff on the trach tube so that some air can pass over the vocal cords.

Another option is a speech valve such as a Passy-Muir that directs exhaled air through the vocal cords. A third option is a “talking trach,” which uses an external source of air to flow over the vocal cords while allowing the cuff to remain inflated.

Similarly, if swallowing safely was possible before the trach, it generally isn’t a problem afterward. However, an inflated cuff may make swallowing more difficult.

A trach often is recommended for those with problems swallowing and aspirating food or saliva into the lungs. The inflated trach cuff prevents aspiration, although anything that goes down “the wrong way” (into the trachea) will sit on top of the cuff and continue on its way to the lungs when the cuff is deflated for speech.

A trach is now available that has a second small tube that allows the area above the cuff to be suctioned, for even better protection of the lungs.

Permanent?

Fears that choosing a trach and vent is an irreversible decision are unfounded.

If the possibility of returning to noninvasive ventilation exists, the trach opening will close and heal when the tube is removed, leaving a scar. (See the “The Great Trach Escape,” September-October 2003, for more information on reversing a tracheostomy.)

If a person decides that quality of life is gone and he or she is prepared for death, then under a doctor’s supervision, medication for comfort can be given and the vent removed.

The bottom line

NIV remains the first and very effective line of defense when breathing problems begin. But if NIV can no longer do the job, a trach and simple equipment upgrade from BiPAP to vent can be a very positive experience.

Never having to worry or even think about breathing or clearing congestion is priceless! Overall physical health improves as much as or more than when NIV was first started. Fatigue is reduced, and nearly everyone (very accurately) feels as though they have taken a giant step back from death’s door.

A trach and vent combination isn’t for everyone, but for those whose quality of life only needs better breathing than NIV can provide, the combination can give years of good quality living.

Diane Huberty of Fort Wayne, Ind., is a retired neuroscience registered nurse who has lived with slowly progressive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) for 22 years. She says her quality of life improved drastically when she got a trach and vent, and her only regret is that she didn’t make the switch a year or so sooner.

Tracheostomy Resources

Breathe Easy: Respiratory Care in Neuromuscular Disorders is available through local MDA offices or online.

Quest articles about respiratory issues include:

“The Great Trach Escape: Is it for You?” September-October 2003

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information