OPMD: Surgery to Help Move Food Past Weak Throat Muscles

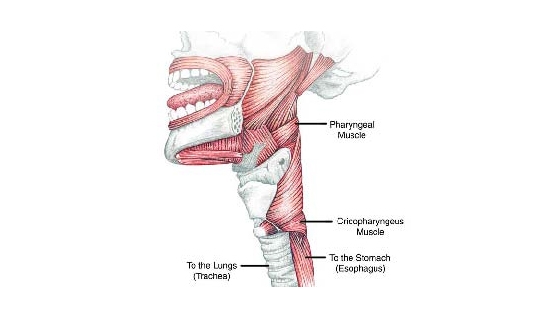

Starting with the tongue and moving down the throat and into the esophagus are a series of muscles that constrict and push food from the mouth to the stomach. The tongue and throat muscles weaken severely in OPMD, leading to choking, inhaling food into the lungs (“aspiration”) and lung infections (pneumonia). Speaking also can be adversely affected by weakening tongue and throat muscles.

Unfortunately, says Albert Merati, an associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, nothing can be done surgically to strengthen the weakening muscles. However, something can be done to weaken the resistance against which they have to push to get food past the throat and into the stomach.

The muscle that surrounds the throat just above the esophagus is known as the “cricopharyngeus,” or CP muscle.

Between swallows, the CP muscle is closed. When the constrictor muscles above it are active (imagine food moving through a snake), it relaxes and opens.

People have swallowing difficulties (“dysphagia”) if the constrictors are weak or any parts of the swallowing mechanism are not coordinated. In OPMD, Merati says, “it’s a matter of loss of strength in the constrictors that can’t be fixed. In this condition, the CP is the only thing we can operate on. The less obstruction there is, even in the absence of good pressure from above, the more easily stuff can go down.” (Imagine widening the narrow part of a funnel.)

There are a variety of procedures one can use to open the CP muscle, ranging from dilation with an instrument, to injections of a muscle-weakening substance, to cutting into the muscle.

Ultimately, if the throat muscles weaken enough so that food or liquids are inhaled into the lungs, the oral route for eating and drinking may have to be bypassed entirely and a tube inserted directly into the stomach.

Some procedures require general anesthesia, while others can be done using sedation or a local anesthetic.

(Muscle diseases in general can sometimes lead to unexpected reactions to inhaled anesthetics or muscle-relaxing medications, so the surgical team should be alert to monitoring the patient particularly carefully during and after surgery.)

CP dilation

The simplest procedure, Merati notes, is dilating the CP muscle with an instrument, known as “cricopharyngeal dilation.” It’s by far the most common treatment for dysphagia related to problems in the upper throat, but it’s temporary, lasting at most a year or so before it has to be repeated.

“It’s done casually in a lot of patients, because it’s convenient, and it’s low risk,” Merati says. If a gastroenterologist is already putting a scope down into the throat to see what the problem is, a dilating instrument can be inserted without adding much risk to the procedure, he notes.

Botox injections

The next step often is injections of botulinum toxin (popularly known as Botox, a brand name). Botulinum toxin, derived from a bacterium, is a poison that weakens muscle, and it can be injected into a muscle for this purpose. “The down side is, it’s temporary,” like the dilation procedure, Merati says, estimating the duration of its effect to be three to four months.

“Some patients who aren’t ready to commit to a permanent solution find it attractive,” he notes. “They can think of it as a trial run for a permanent operation, or they can keep getting Botox every now and then.” Merati says the procedure for Botox injections takes about 10 minutes, and most surgeons like to do it through the mouth, with the patient under general anesthesia.

Some doctors inject Botox through the skin in the throat area, which doesn’t require anesthesia, but Merati says the procedure isn’t as reliable. “If it gets in the wrong place, you can have all sorts of problems,” he notes.

CP myotomy

The definitive operation for OPMD-related dysphagia, and the one that Merati performs most often, is called surgical CP myotomy, which means cutting into the CP muscle.

The operation can be done with either a laser, through the mouth, or with a scalpel, through the skin. Either way, the CP muscle is cut, and its grip on the throat is permanently loosened, making it easier to swallow. The operation requires about a 1.5-inch incision parallel to the collarbone on the left side of the neck and takes a half hour to an hour.

Merati says he’s performed about 100 CP myotomies in his career, about 15 to 20 on OPMD patients. “About 90 percent of OPMD patients respond to surgery to some extent,” he says, “and the majority do very well.” Admittedly, he notes, about a third of people with OPMD will have some return of dysphagia symptoms three to four years after surgery, as their disease progresses.

G-tube insertion

If a patient’s swallowing muscles are so severely weakened by OPMD that food and drink can’t be safely directed to the stomach, and instead routinely go down the trachea into the lungs, then a gastrostomy (“g”) tube can be inserted. A g-tube goes directly into the stomach from outside the body, bypassing the oral route for swallowing entirely.

G-tube insertion is generally performed by a radiologist or gastroenterologist, Merati says. Avoiding eating and drinking entirely is a drastic, though sometimes necessary, step, Merati notes, adding that he often considers doing a CP myotomy even in people who already have g-tubes. In some cases, a myotomy can allow them to drink liquids, with care, even if they’re getting most of their nutrition through the g-tube. At the very least, it allows them to safely swallow their own secretions.

Risks

The risk of eventual treatment failure and return of symptoms in a progressive disease like OPMD is high, Merati notes. “Even if someone is 62 and has an operation and does well, eventually it may not continue to work, as the disease progresses.”

Adverse events, though rare, may also occur. Paralysis of the vocal cords, damaging the ability to speak either temporarily or permanently, is estimated to occur about 1 percent to 3 percent of the time during a cricopharyngeal myotomy procedure, Merati says, although he’s never seen it happen in his cases.

Another complication that Merati hasn’t witnessed but which he notes is possible is a nonhealing wound in the neck through which food or liquid can drain. That, he says, can be fixed, but in the meantime, it can lead to a serious infection.

Gastroesophageal reflux — food or liquid coming up from the stomach into the esophagus — can occur after the cricopharyngeal muscle has been weakened, Merati says, “because you’ve taken away one of the barriers to reflux.” However, he says, it generally isn’t a problem.

Finding a surgeon

Merati advises patients considering surgery to seek out a head and neck surgeon specializing in otolaryngology (the study of the ears and throat) or laryngology (the study of the throat) who has a lot of experience performing procedures to help with swallowing.

For help finding a surgeon in your area, check with the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at www.entnet.org or (703) 836-4444. Or, contact Albert Merati at amerati@u.washington.edu or (206) 598-4022.

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information